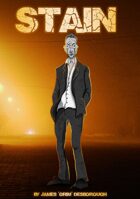

A post-apocalyptic tale, rejected (narrowly) from an anthology. So you get it! Something of a dry-run for a setting for a forthcoming survival game.

A post-apocalyptic tale, rejected (narrowly) from an anthology. So you get it! Something of a dry-run for a setting for a forthcoming survival game.

Days run a little differently now than they used to.

It used to be I would get up, kiss my wife good morning, wake up the kids and head into the shower. Breakfast was a cereal bar and a cup of coffee on the way out of the door to the car. I drove eight miles to town, parked my car, walked to my office and sat in front of a computer from nine in the morning until five in the evening fielding people’s problems with their computers. Then I’d go home for an evening of forcing my kids to eat their peas and watching boxed sets on Netflix in bed with the missus.

A dull, boring, ordinary life. Days ticking by on my phone calendar. Nothing special, the same kind of thing that millions upon millions of people did every day, day in, day out, without changing or straying from the norm.

Now, things are a little different.

I get up when the sun rises, and I let everyone else sleep. I peel back the tarp and climb down the ladder – slippery with morning dew – to the forest floor. There’s no breakfast, we eat once a day, in the evening. I walk the trails through the woods and check the snares as well as the fish hooks we leave dangling in the rivulet – though the water drops every day. If I find any fallen wood, I bring it back to the hide to dry out for the evening’s fire, but that’s getting scarce too. We’ll have to start cutting them down soon, and that will make our presence easier to detect. Then I walk back to the hide, and I sit in the cover under the hide and tinker with the radio, just for something to do. It’s unfixable since the pulse, like everything else, but it keeps me busy.

I don’t know how anyone else lives now, but if they’re surviving it must be something like this.

Somehow we survived the pulse, the chaos that came after it. The plague and the looters, the rioters and murderers. All of us, my whole family.

There’s me, my wife (Ellie) my father (Gramps), and my kids, Tony and Amy.

Tony’s doing alright; he was a scout before everything went to hell and while he doesn’t enjoy camping anymore, he can cope with it.

Amy’s broken, though, and there’s nothing we can do about it. She hasn’t talked since we escaped town and she has her little den she’s dug in the woods away from the rest of us. She only comes close to us when we make food, so at least we know she’s eating. We keep hoping she’ll snap out of it, but she hasn’t yet.

My wife was a fiercely independent woman before all this happened, the one who did everything made more money than me doing bank work in the city, organised and ran our lives. Now she’s lost, traumatised, just doing what she has to and crying over everything we’ve lost.

Gramps is old, sick, but he struggles on and helps me as best he can. He’s a tough old dog, my father but we all notice the cough. Sick as he is I’ll dread it when he’s finally gone. He’s used to a simpler world than we were. He’s practical; he knows how to fix things, how to skin rabbits and gut pheasants, skills which have become literal lifesavers. I’ve learned more from him in this past year than in the forty preceding it. I used to be the one to teach him things like using the internet or setting the video to record. It’s strange how things turn out.

We lost track of time in all the chaos but so far as we can tell it’s late summer now, maybe the end of August. We’re hoping we can find and preserve a lot of autumn fruit and nuts, somehow, once they start to appear. We can’t get meat to smoke or dry properly, we’ve tried we have no salt or vinegar or even alcohol to pickle or preserve with, and we daren’t go back to town to look for supplies that probably aren’t there.

It’s a worry.

This morning was the first in quite some time that there had been a chill in the air and mist clinging to trees. It was getting towards the autumn, and that weighed heavy on my mind.

We had a rabbit in a snare, so that was a good haul for the morning or at least better than nothing. The hazelnuts weren’t ripe yet, by any stretch, so that was a bust, and the blackberries weren’t ripe yet. I still had some gloves and a good knife, so I cut a big bushel of stinging nettles – they come out a bit like spinach when you boil them. We’re all utterly bored of them, though, we lived off nettles and rice too many days before we got the snares right. Just as well that they did, because we ran out of rice. I read once you can’t live off of rabbit, but that’s been almost all we’ve been eating this month other than the nettles. Another thing to worry about.

When I get back on this day, everyone’s up and awake. My grubby little family of dirty survivors. No sign of Amy though, at least not yet, no food for her to eat I suppose. My wife’s hanging up the blankets to try and dry and air them in the sun – it hardly works even in the summer, you just can’t get dry living outside. Gramps is fiddling on that bow of his again – bailing twine and hazel sticks don’t make for the best or most accurate hunting weapon, but he perseveres. Tony’s tending the fire; that has become his singular obsession. He keeps it going through the day from the embers of the previous night. He’s gotten pretty good at it, though we don’t dare have a massive fire. Someone might see.

The day passes, somehow. Boredom is something we all constantly experience now, boredom punctuated by terror at the noises coming from the woods. We’ve not seen another person in months, just deer and the occasional fox sniffing around. We still remember what it was like getting out of town. People were – and probably still are – terrible. Desperation does that to people. It has done it to me; there is blood on my hands as much as anyone.

When the sun starts to set, we build the fire up, boil the river water in our fire-blackened pot and put in the rabbit and the nettles. It’s not much, but its something, or will be when it’s cooked.

Tomorrow, maybe, we’ll have some better luck.

Only we don’t get to tomorrow uninterrupted. There’s a loud cracking sound from the edge of our little clearing, our home, and then a voice raised, calling out to us. A new voice, one we haven’t heard before, cracked and husky with a lack of practice at speaking.

“Can you spare a little of that?”

***

He looked a state, but then we all did. He’d made an effort to trim his beard, which I hadn’t, but he was still as grubby and tired looking as the rest of us. Layered with muck and sweat, the sort of thing you only ever used to see on homeless people. He had a huge backpack, one of those army ones called ‘Bergens’ I think, and a gun, something I hadn’t seen in a long time. It was a battered looking double-barrel, and he had a half-empty bandolier of shells hung around his neck. It was pointing down, but he was almost as cautious as we were, frozen in place around our dinner with only gramps and his stupid bow and arrow to defend ourselves.

“I’ve got salt, pepper, some spice. Just nothing to put it with, can we make a trade?” He took a cautious, half-step forward, holding the gun one handed, raising the other, palm towards us.

Just the thought of salt had me salivating, let alone anything else. My stomach yawned at the mere mention. Less food, but with flavour? That would be a good trade at this point and someone who’d been out there might know something. News and flavour. I stepped forward and waved gramps to lower his bow – for all the good it could do in the first place.

“If you put the gun down and show us what you have, maybe we can find a place for you tonight and a bit of food. It’s just rabbit and nettles, though. Nothing fancy.” I moved, slowly, between him and my family. If things went wrong, perhaps I could still protect them.

He set the gun down on a stump with the shells and unslung his pack, keeping one hand up as he rummaged in the side pocket. He showed us salt, pepper and – Lord have mercy – garlic granules.

“Alright, come on closer but leave the gun there,” I gestured to him to approach, and he set his pack behind and came forward.

He stank worse than we did, or we’d just gotten used to our smell perhaps. We could wash – occasionally – in the rivulet, but he smelled like he hadn’t washed at all in the year since the pulse. He was greasy with it. Shiny-headed in the firelight and the fading sun, and I could hear his stomach growling as loud as mine was. He handed over the condiments, and I gave them to Ellie. She added them to the stew pot with shaking, quivering hands.

“It won’t be ready for a while. Why don’t you sit with us and sing for your supper?”

He winced a little at the suggestion, but he did sit, on one of the mossy logs we’d dragged here to use as seats and after a deep sigh he told us his tale, constantly glancing towards the pot and the promise of food to come, as though reassuring himself it was real.

“What do you want to know?” He asked, his voice low, almost lost in the crackling of the fire.

“Your name,” I sat, opposite him and everyone else crowded closer. “Everything you know. What’s been going on out there, how did you survive?”

He tongued his lips and took a sip of water from his canteen, and then he began to talk, a practised tale he must have told many times before. Too many people.

“My name’s Alan. I was a delivery driver. My watch didn’t work; my phone didn’t work, the van didn’t work. Nothing worked. I waited for other cars but after an hour all there was, was a young couple whose own car had broken down. That seemed like a bit too much of a coincidence to me, but I stayed with the van. Like an idiot.

He shook his head and plucked a few leaves off his boots before he went on. “Wasn’t until a policeman on a bike – of all things – came by that I clicked something bigger was going on. His suggestion was to find a pub or something to stay at, but I didn’t. I stuck with the van. I thought it might all get fixed I suppose. Two days later and nothing but a few people trudging down the road. Got to the point where I started breaking into the packages to look for food and drink, but eventually, I had to lock up the van and get going again.”

“We were in town when it happened. It was worse in a lot of ways, though people were looking out for each other at the beginning.”

“Then the sickness hit,” he sighed again, deeper. “As I’m sure you know.”

“We didn’t see much of it; we decided to leave town after a couple of days.”

“You were lucky then. I walked through a couple of villages before I got to a town and by the time I got there, the sickness was in full force. Pale people, white as sheets, barely able to move for how weak they were. Easy prey for the people who were still fit and were looking to loot and pillage. Whatever it was, I didn’t want to catch it. I stayed long enough to get some supplies and then got the same idea you did, to get out.”

I nodded along with him as we shared a moment of understanding. It had been horrible, and it had felt like there was no choice but to get away. We’d seen the writing on the wall the same way he had. Still, leaving people to die was haunting.

“I tried a couple of camping sites, but the sickness or bandits, or worse, always came along. Things broke down or just stopped working – whatever machines were left that is. The amount of people around got fewer and more sparse and spread out the more time went on. I just kept on moving. You’re the first people I’ve even seen a sign of in a few weeks.”

“Worse?” that worried me, I thought we’d seen the worst this new world had to offer.

“Ah, forget it. Don’t worry. Just being dramatic I suppose. I’ve just stayed on the road; there is still food and supplies out there if you’re not too fussy. Dog food will keep you going in a pinch. There’s hunting if you’re a decent shot, but I’m not,” he laughed, a little bitterly. “You seem to be doing alright, though. I’ve been watching you since this morning. You and your family have it pretty good.”

“It doesn’t feel like it most days,” I turned and looked to Ellie as she hovered over the pot. She nodded.

We had plastic bowls from an old picnic set, enough for everyone, though they were no longer the cleanest. The stew was thin and sloppy, but with the salt, pepper, and garlic it was the grandest feast we’d had in some time, considering a single rabbit don’t go so far between so many people.

After a mouthful of boiled rabbit and soggy nettle, Alan stopped abruptly, eyes wide and white in his grubby face. He swallowed, hard, and jabbed one dirty finger at the bowl we’ve filled for Amy. “Why are there six bowls?” He sounded panicked, scared, terrified. We didn’t understand why, but the fear was infectious.

“My daughter. Amy. She’s not well. She hides in the woods, but she comes back for meals. What’s wrong?”

“No, no, no!” He’s clutched his head like it was about to split, set down his bowl and stood, casting about and then walking towards his gun with quick strides.

“Wait no!” I spilled my bowl as I got up. “Don’t hurt us!”

He snatched up the gun and the shells and looked back at me. “I’m not going to, but six people is too many. I didn’t know about the girl. It always goes bad when there’s more than five. Always. Always.”

There’s a subtle change in the air as he says it. His fear is genuine, and it does feel like something has changed, shifted, a chill, a sense of being watched. I can’t explain it.

***

Alan kept staring into the woods, clutching that shotgun of his, white-knuckled and panicked but nothing was happening. My family huddled together in the dark except Amy who had scuttled back into the woods to hide. Slowly the tension began to evaporate from the terror he’d induced in us, and I stepped away from the others to try and talk some sense into him.

“Alan, please, you’ve scared everyone. Nothing’s happening.”

“It will,” he looked back at me with wild, feral eyes. “It’s coming.”

Something about the way he spoke made me still believe he meant what he was saying; I swallowed to wet my throat and ease my voice. “I’ll climb up into the hide and see if I can see anything.” He nodded to me and kept staring out into the trees.

I moved away from him, with a glance towards my family for mutual assurance, and then I stepped to the ladder. When I set my hands on it, it felt strange, dusty under my fingers and when I placed my weight on the bottom rung, it simply snapped, rusted through. That was absurd. It was steel; it had held firm as long as we had been here and showed no sign of breaking or damage. I just stared down at the fragments at my feet, uncomprehending. “Rust?”

“Rust?” Alan twisted around to look at me. “Get clear!” He shouted, stabbing a finger to point up at the hide.

My family moved the moment he barked; I didn’t. I was frozen, staring at the ladder, the patina of rust spreading across it like a time-lapse image of mould running across fruit. I looked aside to the great wooden beams that held the hide up above the forest floor and there too the metal bolts that ran through it and held it all together was turning red-brown and crumbling before my eyes. As I looked up in terrified wonder, the hide gave a loud groan, shuddered and slewed drunkenly sideways.

Our home, everything we had scraped, preserved and recovered was smashed to pieces in a deafening, splintering crash as it toppled into the woods and threw up clouds of dirt and leaves in all directions, blowing our meagre fire across the forest as embers that quickly vanished in the dark.

My ears were ringing. My lungs were burning as I coughed up leaf mold and ash. I stared into the crater around the broken stumps of the support columns as the clouds settled and thinned and saw something even stranger. The ground was writhing, twisting, heaving with worms, one atop the other in an enormous tangle right where the hide had stood. I’d never seen anything quite like it. The rust, the worms, none of it made any sense. At all.

“Alan! What the hell is this?” I screamed at him over my deafness, and I staggered to check on my family. They were horrified, staring at what remained of our meagre life, backed against a grand, old tree.

“This is what I meant by worse,” he yelled back. “Come together, help each other, and the world turns against you. I thought we were safe! I didn’t know about the girl!” The despair in his voice made my spine quiver.

I held Ellie tight though there was nothing I could offer to calm her, no platitude that would serve in this situation. Every last little thing we’d scraped together, this hardscrabble desperate life we’d forged, ruined in an instant.

Tony stepped apart from us, peeling away from the family huddle, clinging with one hand to my ragged shirt and staring into the night. Suddenly pointed out, with his free hand, past Alan, out into a gap in the trees to the blue-black night sky and the distant stars. “Dad! Look!”

I looked where he was pointing, and through the gap in the trees, the sky abruptly turned completely black. With sudden ferocity a torrent of croaking, shrieking feathers came pouring through the trees like a tidal wave. A pecking, screaming mass of crows that scratched, flapped and snapped at us as they flew around and over us and circled back through the trees and into the sky to fly back at us again.

I was bleeding from dozens of cuts and scratches, as was everyone else. Blood ran from a gash in my brow, down into my eye, half blinding me as the birds wheeled and whirled through the trees, screeching and cawing, massing for a second attack. It was incredible, it was impossible, it was terrifying, but there was no time to think about it. As they swept back I grabbed for my wife and son and hit the ground, scrambling under what remained of the tarp as Alan’s shotgun barked deafeningly, and flashes of light lit through the plastic.

Ears ringing I could barely hear the bodies of the crows tumbling around us, some still twitching and squawking in pain, crippled or killed by a shot, others tearing at the tarp with their claws and beaks to try and get at us. There were sickening crunches, something smacked into my leg and bruised it to the bone, but most of the crowing stopped. We screamed as the tarp was thrown back.

It was Alan, bloodied, blinded in one eye, a ragged hole where it should have been. The crows that remained perched angrily in the trees; the ground was littered with their corpses. Blood and spittle dripped down his chin as he opened the gun and thrust in the last shell. “It’ll be people next I think. Bandits. It won’t stop. It won’t ever stop so long as we’re together.”

I struggled to stand, the bruised leg almost giving way under me. “We’ll run, there’s nothing to stay here for anyway. Come with us. We’ll make it together. Don’t be stupid.” I reached my hand towards him, bloodied and scratched, fingers stretched out to take his hand.

He just shook his head and looked at me with one working eye and one ruined one, blood running down his face. “No. It won’t work. No more than five people. Never more than five. There’re no antibiotics anyway. I’m done. Thanks for the rabbit. I should have seen the girl.” Tears mingled with the blood.

Before I could stop him, he twisted the gun and fired. The flash was so close it singed my eyebrows and blinded me for a moment as his mostly headless body fell back with a wet, boneless thump amongst the dead crows.

We stood, I don’t know how long, in shock. When we recovered our senses, and our muscles answered our appeals to move the surviving crows had left, and it was quiet again. The air had changed, back, to the way it was before, without that tension, without that sensation of being watched. A new peace settled over our shattered camp and then, after a time, as we had so many times before, we set about picking up the pieces of our shattered lives.

***

We’re back on the road now. All five of us. Amy came back out of hiding after Alan died though she still hasn’t spoken and never leaves her mother’s side. We have Alan’s supplies and his empty gun. We have a tiny bit of food, the last gasp of the snares and fishing lines, but autumn is coming now, and there’ll be nuts and berries and whatever has survived in people’s abandoned gardens for a while.

We’ll look for supplies in some of the forest villages and then try to find somewhere remote and sheltered where we can rest up for the winter. All five of us. Just the five of us. Wherever we go, I’m going to leave this information, no more than five. Maybe it’ll keep some other people alive, but it means we’re alone, and we have to stay alone if we’re going to live. It means there’s never going to be any more help. No civilisation. Nobody to ride to the rescue or to rebuild.

It’s just us now.

Just family.

Read Full Post »

All the cool kids are doing it. So I set up a Discord server.

All the cool kids are doing it. So I set up a Discord server. The complete playlist of Inside Gamergate is up.

The complete playlist of Inside Gamergate is up. A post-apocalyptic tale, rejected (narrowly) from an anthology. So you get it! Something of a dry-run for a setting for a forthcoming survival game.

A post-apocalyptic tale, rejected (narrowly) from an anthology. So you get it! Something of a dry-run for a setting for a forthcoming survival game. I think I’m uniquely positioned to give an interesting take on what happened. I know the history, I can properly contextualise it within a timeline of other moral panics and responses. I participated in Gamergate. I’ve seen the aftermath of it. I’ve seen how it influenced things and how it fits into the broader culture war that has characterised the twenty-teens. I’ve been targeted by its enemies, who like to portray themselves as good people, and are anything but.

I think I’m uniquely positioned to give an interesting take on what happened. I know the history, I can properly contextualise it within a timeline of other moral panics and responses. I participated in Gamergate. I’ve seen the aftermath of it. I’ve seen how it influenced things and how it fits into the broader culture war that has characterised the twenty-teens. I’ve been targeted by its enemies, who like to portray themselves as good people, and are anything but. Gamergate was many things to many people, depending on their perspective. For some it was a harassment campaign, even terrorism, for others a key fight for ethics, against censorship.

Gamergate was many things to many people, depending on their perspective. For some it was a harassment campaign, even terrorism, for others a key fight for ethics, against censorship.